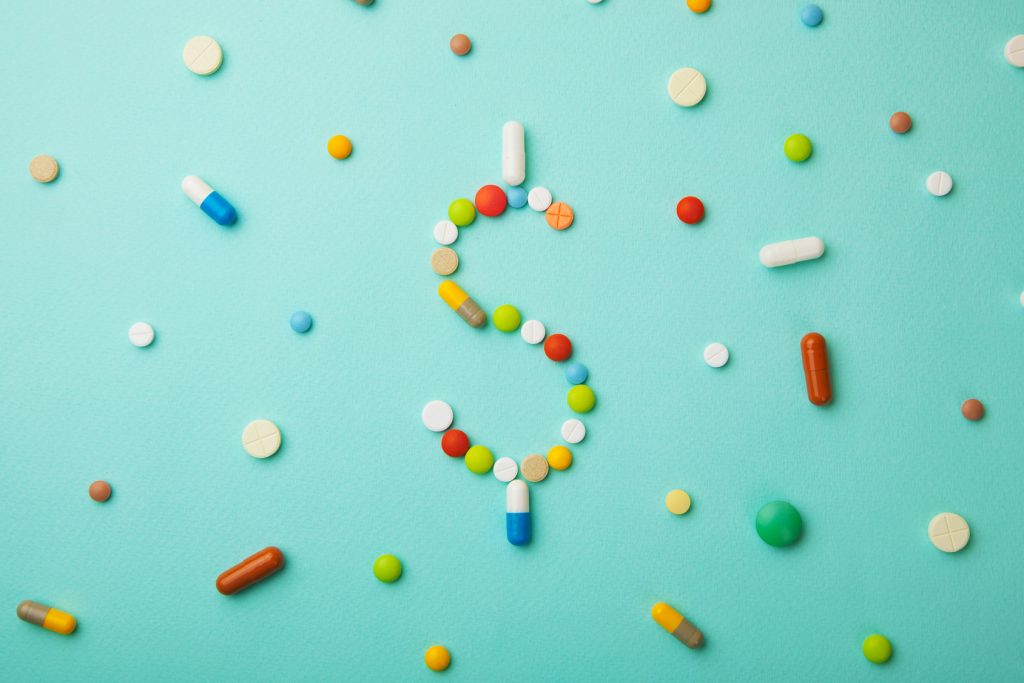

drug prices

TagGlobal Pricing Plan Added To Trump’s Attack On Drug Prices, But Doubts Persist

The proposal would have Medicare base what it pays for some expensive drugs on the average prices in other industrialized countries.

TV Ads Must Disclose Drug Prices, Trump Administration Says

The Trump administration proposed a new rule this week which demands drug makers disclose list prices for medications in their TV commercials.

Pharma Sales Growth Tied to Price Hikes

Of the roughly $23.3 billion in sales growth seen by 45 top pharmaceutical products, $14.3 billion of that has been tied to price increases, not demand.

Congress Bans Pharmacist ‘Gag Orders’ On Drug Prices

Pharmacists will no longer have to keep it a secret when the cash price for a prescription is less than what someone would pay using their insurance plan.

Drugmakers Play The Patent Game To Lock In Prices, Block Competitors

Drug companies typically have less than 10 years of exclusive rights once a drug hits the marketplace. They can extend their monopolies by layering in secondary patents.

Insulin’s Steep Price Leads To Deadly Rationing

The price of insulin in the U.S. has more than doubled since 2012. Because of this, some diabetics have been forced to take drastic measures, like rationing their insulin.

New Guidances Issued to Promote Generic Drug Access and Drug Price Competition

The guidances issued today by the FDA are part of a larger initiative by the administration to increase patient access to high-quality generics.

Trump Administration Sinks Teeth Into Paring Down Drug Prices, On 5 Key Points

Three months after President Trump announced his blueprint to bring down drug prices, administration officials have begun putting some teeth behind the rhetoric.

New FDA Commissioner Gottlieb Unveils Price-fighting Strategies

The FDA can’t regulate drug prices, but it can implement measures aimed at deterring the types of price hikes that have made so many headlines over more than a year.

Taxing Drug Price Spikes: Assessing the Potential Impact

How a proposed tax penalty on drugs with price increases exceeding the inflation could impact patients, public insurance programs, and innovation.