advanced practice

TagReport: PAs/NPs Provide Similar or Better Care than Doctors

A new report from a World Health Organization team indicates that non-physicians, such as PAs and NPs, provide comparable care to that of physicians.

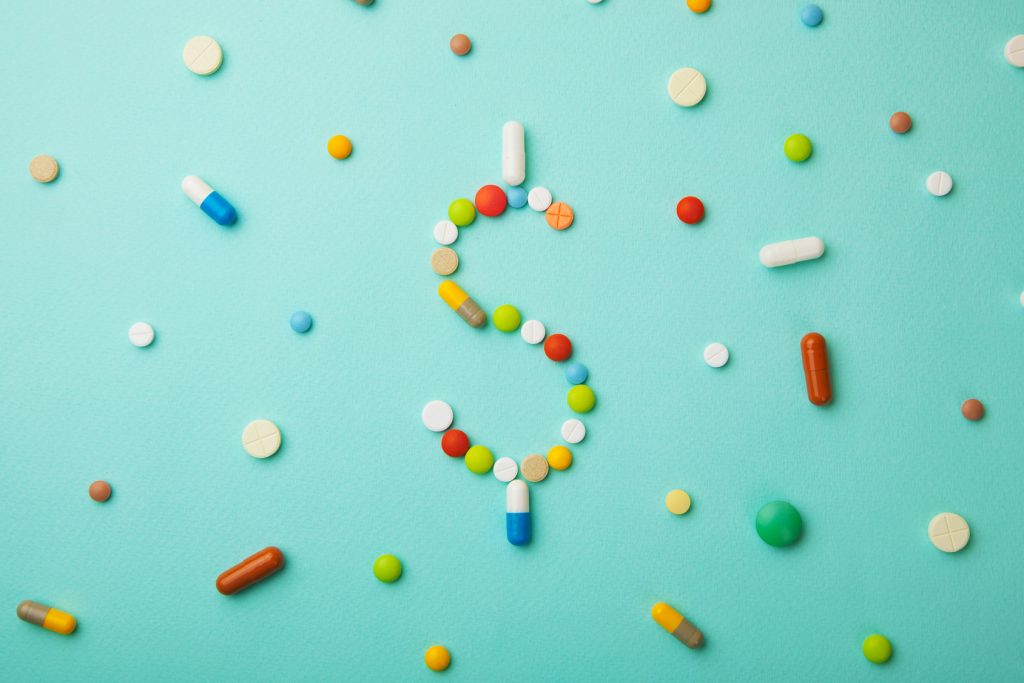

APRNs and PAs Ranked Among Highest Paying Jobs in Healthcare

Advanced practitioners are enjoying advanced wages, and two spots on a new top ten list of the highest paying jobs in healthcare.

Kim’s Blog: “See You Down The Road”

How do you ask patients about end-of-life wishes? Kimberly Spering, MSN, FNP-BC discusses her experience with having this crucial conversation.

Demand for Newly Certified PAs is Strong

Demand is high and the job market is strong for newly certified PAs, according to a new report by the National Commission of Certified Physician Assistants.

Kim’s Blog: What If The Priority of Our Visit is Addressing Social Needs and Non-Compliance

Kim Spering encourages you to look for the real reasons patients don’t show up on time, don’t take their medications, and seem to go against medical advice.

Entrepreneurship for Clinicians

Have you ever thought there might be more to your career than clinical practice? Explore the idea of entrepreneurship with Jordan Roberts and Dave Mittman.

Three Ways to Celebrate PA Week

Here are three ways to celebrate PAs, while also raising awareness of the profession’s significant impacts on healthcare, from October 6th through 12th.

New Legislation Arms Advanced Practitioners in the Fight Against Opioids

More than 115 Americans die every day from opioid-related causes. The SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, which passed in the House last week, aims to stop that.

Steal this Recruiter’s Tips to Land the Perfect Job

Seeking a competitive advantage to help you land your perfect job? Look no further than this advice from a clinician who has been involved in hiring.

Using Medical Survey Panels to Grow Your Clinical Income

Explore the benefits, as well as the downsides, of participating in medical market research survey panels as a way to supplement your income.